A Caveat

I am not a lawyer nor a professional negotiator. This is one citizen’s view of a situation that has deep and complex ties to the history of First Nations and colonial settlers on this Island known as Vancouver Island. I deeply respect and acknowledge every First Nation’s right to self-determination and sovereignty over lands that were stolen from them without treaty or recourse.

The Question of the Railway

Update November 6 2024: Yesterday I made this video on the topic as the Snaw-naw-as Nation remove the tracks from their reservation lands.

Over the past five to ten years the dominant question facing the Vancouver Island Railway has been the right of First Nations to assert sovereignty over the former E&N lands and potentially have that land returned if the railway is not to be used.

The Snaw-naw-as First Nation made this claim formally in court in 2018 and a decision was made in 2021. You can read a summary of that case here.

The Crown (BC and Canada) was essentially given a deadline by the Courts of March 2023 to either commit to revitalizing the railway and thus denying the ability of Snaw-naw-as to regain the land, or admit the line would not be used and have the land be reverted back to First Nations control.

What the Government actually chose to do was a bit of both. The Federal Government decided to give that portion of the land back to the Snaw-Naw-As as “the first step in the process of developing a shared vision for the future of the corridor with First Nations.”

“Snaw-Naw-As gets their land back”

The Provincial Government (Minister Fleming) said, “If the corridor is broken up and built over, it will be lost forever, and future generations will likely be unable to assemble a continuous transportation corridor of land like this again”.

The reaction from the First Nation was instructive. The lawyer for Snaw-naw-as said “The Island Corridor Foundation has been hanging on to this dream that one day there will be train service along the corridor again. And that could still be the case. But at least now Snaw-Naw-As gets their land back.”

That is a hopeful statement, both for railway activists like myself, and for First Nations who are working to get their land back, something railway activists should be supporting as well.

Canada: Splitting First Nations since Colonization

Look at pretty much any major Indian Reservation in Canada and you’ll see a major roadway right through it. Not only did Canada take First Nations off of their traditional, expansive, territories gained over thousands of years, often (especially in BC) without treaty, and stick them into small postage-stamp “reserves”, they even made those reserve smaller over time and criss-crossed them with railways, roads, and highways.

I can think of a dozen examples on Vancouver Island alone. Here’s a short list just in the central Island area:

- Qualicum Bay – Qualicum FN – bisected by Highway 19, 19A, and Island Railway

- Port Alberni – Tseshaht FN – Highway 4

- Port Alberni – Hupacasath FN – Highway 4

- Nanaimo – Snuneymuxw FN – Island Railway

- Nanoose – Snaw-naw-as FN – Highway 19 and Island Railway

There are many other examples all the way up and down the Island from Port Hardy to Victoria and the West Coast.

The Snaw-naw-as Solution (and perhaps others) – Hand back land – Realign the railway -Improve Transport Corridors.

Again, I will caveat this as only being my opinion and suggestion. This is a question that must be decided first and foremost by the wishes of the First Nations involved. However, I do believe that the vast majority of First Nations and non-First Nations people alike want the same things: Real reconciliation (based on BC-DRIPA and UNDRIP); land back; and sustainable transportation in the railway as an alternative to our ever-filling, climate-distratous, dangerous and expensive, highways.

Nanoose Case Step 1 – Recognizing the History

“he had been away fishing and when he returned he found the road way across the Reserve”

The history of Nanoose Bay

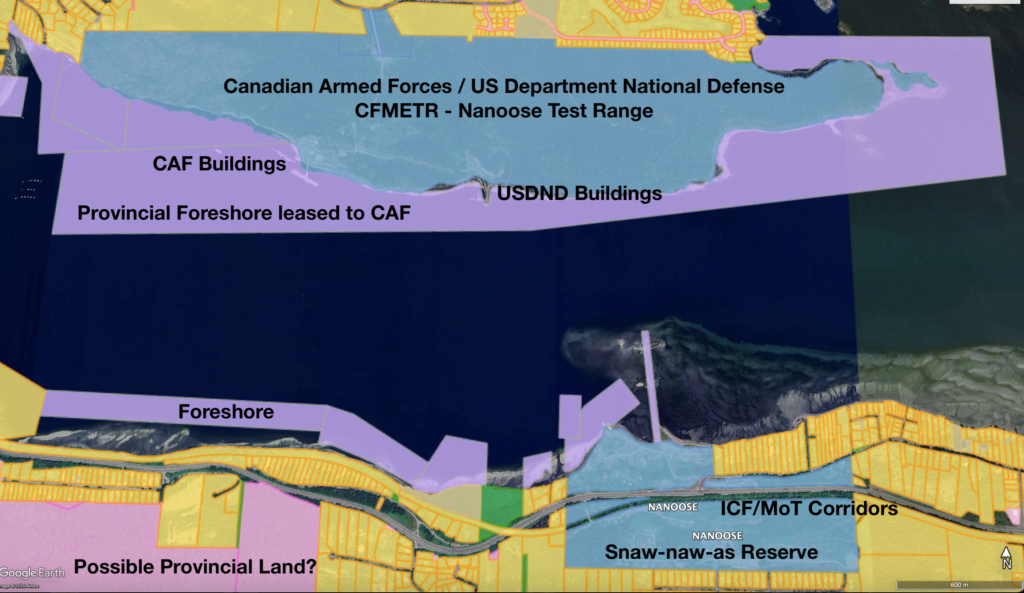

The Google map below is a little busy, but it shows the ownership and state of the land today.

While researching for this post I came across the book, “The History of Nanoose Bay” second edition published in 1980. It includes this map, presumably from around mid-century though it is not clear.

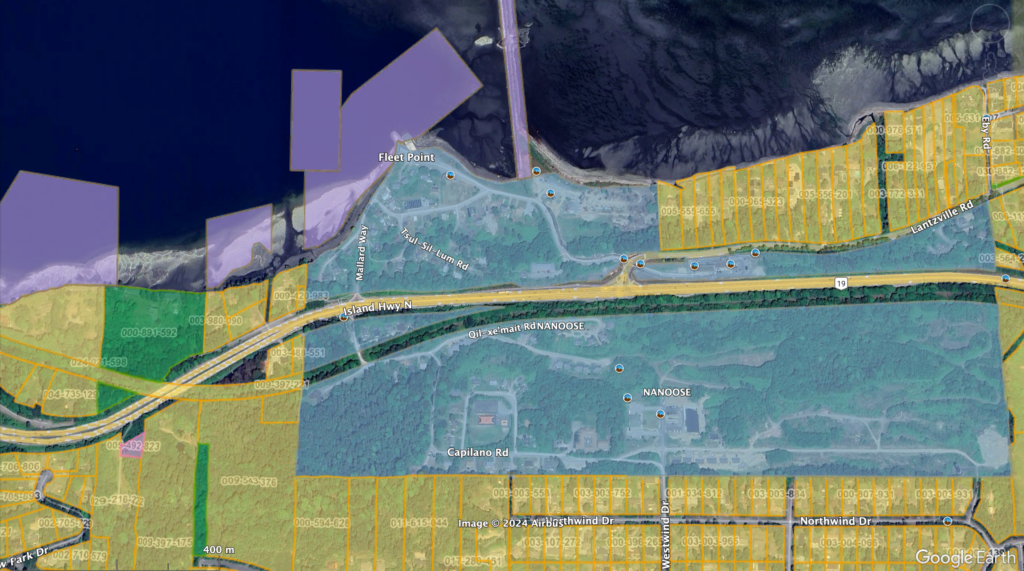

Here is the area zoomed in a little more:

On Page 8 of the book it states:

“The Nanoose Reservation is crossed by the Island Highway and the E & N Railway. It is reached by Eby Road which forms part of the eastern border. The Joint Reserve Commission, federal and provincial, established the Reserve on the 15th of December 1876. A survey followed in 1878. Originally, there were 209 acres, but that area has now been whittled down to 160.92 acres. W.H. Taylor bought 30.30 acres in 1932; 10.78 acres were taken for the railroad right of way; and 7 acres for the original Island Highway right of way. The Indians sold the land to W.H. Taylor because they needed the money to make necessary repairs to their houses. They also put in fences and restored the old cemetery. They were not paid for the right of way for the railroad. Their chief, Louis Bob, was given a construction job, but the band did not benefit. No one consulted the Indians about the highway. Chief Wilson Bob Sr. said he had been away fishing and when he returned he found the road way across the Reserve.”

The book goes into depth about the Snaw-naw-as history in that particular place, on both sides of the Bay, and their traditional hunting, fishing and other pursuits gained over millennia. All of these were taken away from them by the settlers and colonial government. It is clear that this needs to be rectified.

Step 2 – Land Back – The Military Base

The obvious answer is to give the land back, and the obvious place to start is the Federal Government lands across the Bay which were of course all originally Snaw-naw-as territory.

As part of this arrangement, and in addition to monetary compensation, the Snaw-naw-as should be given back all of the land currently controlled by the Crown, including foreshore, on the north side of Nanoose Bay except for the immediate area (example in the red box) of the base itself.

I would suggest that would be the minimum.

Step 3 – Realignment of Highway 19 and the Island Corridor

The portion of railway land running through the reserve is very small, but obviously disruptive, and also obviously done without any consent. That said, I think it is reasonable to suggest the highway itself is now a permanent structure.

The good news is the highway and railway are very nearly adjacent to each other all the way through the reservation. You can see the map below that the ownership has been updated. The railway right-of-way is not shaded, either yellow as privately owned like the rest of the railway, nor is it blue, indicating federal or reserve land. This land is in flux.

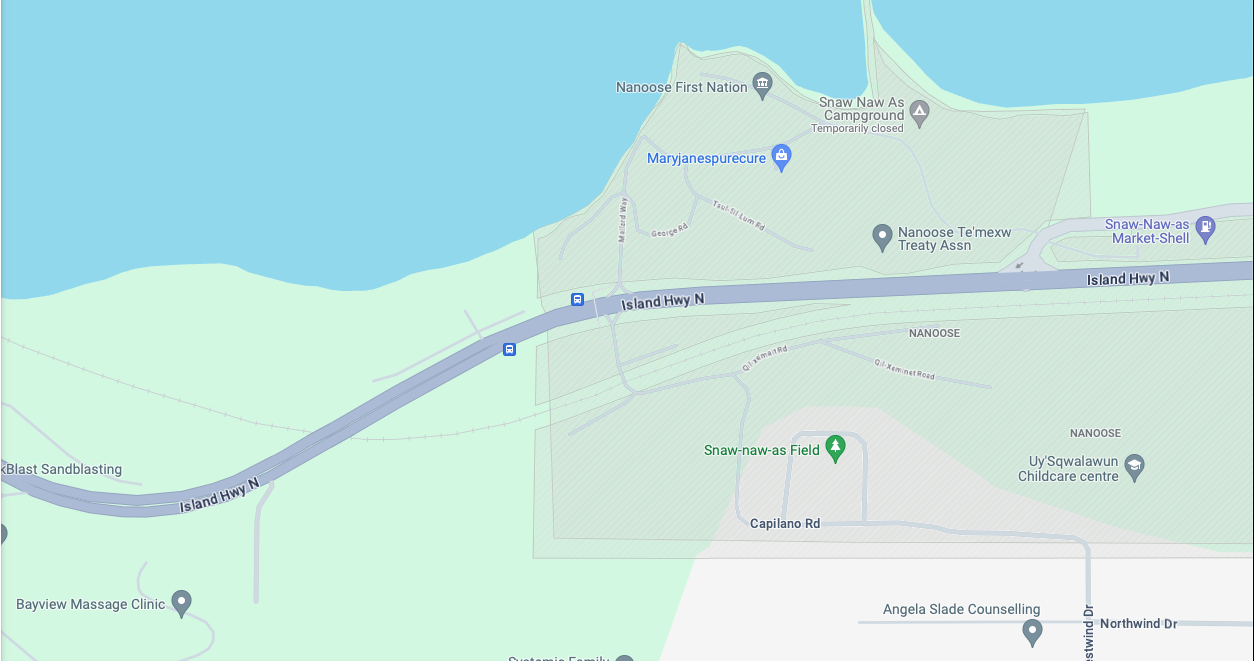

My suggestion would be to realign the highway and railway so that they are truly adjacent to, and even on top of (you’ll see), each other from the southeast end of the reserve near Superior Road all the way to where the railway passes under the highway to the northwest.

If you look at other highway projects, be it the Highway 1 Mackenzie Interchange in Victoria, the Highway 17 bypass in Vancouver, or the Coquihala Highway after the Atmospheric River disaster, you would recognize that this kind of realignment is not only very possible, it’s relatively simple to design and build.

This portion of the highway is also in need of improvement. There are historic and ongoing safety concerns for all road users and pedestrians/community members trying to move from one side to the other.

The comparison below shows the existing highway and then the railway (which is currently just behind the trees) moving gradually down to the same level as the highway, hopefully with a minimum number of trees removed in the process. The highway itself would need to be realigned slightly to the north (right in this picture) to accommodate the railway on its south side and to retain access to McKercher Road.

The stretch between McKercher and Lantzville Road would be almost unchanged save for the railway being directly adjacent. In the comparison below is the current Nanoose area with the after comparison being to Highway 1 just east of Bridal Falls where the railway is very close to the highway.

By the end of this rebuild of this section of railway and highway, there should be better/safer crossings for the First Nation to access the two sides of the reserve, and the E&N and Highway 19 use the bare minimum of space.

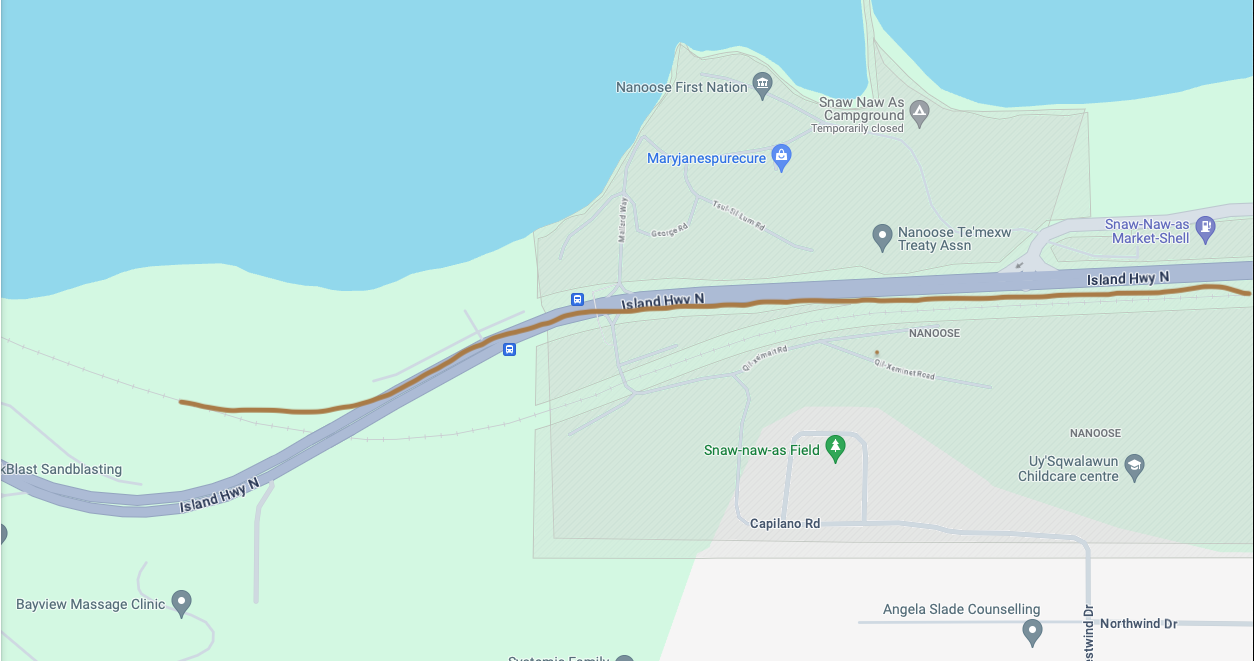

At Ladysmith Road there should be a new overpass or underpass created to facilitate safe and wheel-accessible access for First Nations Reserve residents to and from the two sides. The railway is in brown.

The area in need of the greatest amount of work will be the northwest end of the project where the E&N would make a new crossing of the highway right of way toward Nanoose Bay including the rebuilding of the Capilano Road access and pedestrian access. A new elevated section of highway would need to be built between roughly Capilano Road and the end of the existing Railway overpass.

This is too complex for me to demonstrate with a two-dimensional map as there would need to be two “layers” of transportation corridors but this would be the general location.

This is already a steep section for the Island railway as it drops from a level above the highway at Capilano road to 10 metres below the highway in just 500 metres of track. There is also a “dip” in the roadway itself. A realigned corridor, while needed to satisfy the requirements of this project, could also ‘flatten’ that grade for both the railway and the roadway, resulting in a more efficient and safer experience for all users.

As a comparator I have used the Highway 19/1 interchange in South Nanaimo as an example where one highway passes overtop another. The Island Corridor would represent a narrower, but perhaps longer, corridor and passing. The road, bus, and pedestrian access to and from Capilano Road and the other accesses there would need to be redesigned and improved but this also might lead to safety improvements if there was less opportunity for people to cross the highway on foot.

A Typical Highway Project – Expensive but not Unexpected

Nothing about this project would be insurmountable or unprecedented in the experience of the Ministry of Transportation. If we use the example of the McKenzie Interchange on Highway 1 in Victoria which had a final bill of approximately $96 Million, then with recent inflationary pressures we could expect this project to require anywhere between $100 Million to $200 Million to complete.

In the grand scheme of major projects, this cost would be in line with other major realignments and upgrades to road infrastructure in the Province of BC.

While the standard highway project serves just one laudable purpose, to improve road access, this project would:

- Advance BCDRIP/UNDRIP responsibilities with First Nations by giving land back and minimizing harms from historic transportation decisions.

- Improve and make Highway 19 safer and more efficient

- Improve and make viable the Island Corridor railway

It is my hope that this vision can be attained to the benefit of all.